Deserving or undeserving?

Deserving or undeserving? Governing ‘migrant irregularity’ and squatting in Amsterdam

20 November 2019 was a day of worry and preparations at the warehouse (Bijlmer, Amsterdam). That warehouse was then home to approximately 100 young men from Gambia, Nigeria, Burkina Faso and Senegal. An eviction was planned at 9 am the next day. The young men were classified as “undocumented people,” even though their legal statuses and migration pathways could hardly be lumped together under a single label.

Some of these men had gained protection from Italy but moved to the Netherlands in search of better job opportunities; others had been rejected by Italy or other Member States and wanted to apply for asylum again; yet others were defined as "out-of-procedure" by Dutch authorities, as they had exhausted all avenues for regularising their status.

On the eviction day, the migrants were prepared: personal belongings, mattresses, and food had already been taken out of the warehouse when the police arrived. No resistance. “We are tired. We'd better die,” someone said. Others took it more philosophically: “It's always the same story anyway. Tomorrow we'll see”.

After the eviction, the group dispersed to various destinations across the city, depending on their existing networks or the support they received from volunteers and local associations. However, none of them could be hosted in the facilities of the new national program for sheltering undocumented people called the LVV (Landelijke Vreemdelingen Voorziening, literally "National Aliens Service") that Amsterdam was testing at the time. Most of them did not meet the program's requirements.

What was the aim of the programme, and who was considered deserving enough to enter it? These are some of the questions that our study, recently published in Cities, attempted to answer.

When we approached the LVV program as foreign researchers, we were somewhat surprised by the open-minded nature of a programme that was providing services to the "undocumented", a group of people often considered to be formally "non-existent" and by definition "undeserving" of any public service. This reflection is even more critical today, given the recent top-down propositions to completely stop any reception facilities for undocumented migrants in the Netherlands. City representatives were hopeful about the program’s potential for coping with the city’s growing population of undocumented people, estimated at around 15,000 and many are still fighting today to try to maintain the basic services that the LVV allowed to provide for some.

However, the more we studied the program and its more or less direct effects, the more we also noticed some of its problematic implications. In particular, our study suggests that the pilot program introduced a new "hierarchy of deservingness" among undocumented migrants, effectively reinforcing at the local level the justifications for exclusion from basic services and territorial expulsion.

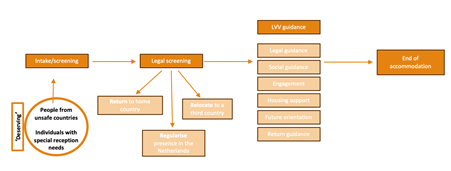

At the core of this new reception system and its "hierarchy of deservingness" was the “durable solution scheme” (RegioPlan, 2020), a model also used in other contexts to manage undocumented migration (see Cole, 2015, for a critique). This approach made it clear that reception is not indefinite; instead, it aimed to resolve irregular status through one of three options: Returning to the country of origin, regularising status in the Netherlands, or relocating to a third country outside the EU that guarantees permanent residency.

Figure 1: The LV pilot program: the 'durable solution scheme'

A closer look at the "durable solution scheme" reveals why LVV imposes stricter selection criteria than the previous local shelters (the so-called BBB, Bed-Bad-Brood shelters), creating a new categorisation among undocumented people. Those whose irregular status is deemed irremediable under national asylum rules are excluded from the program. The LVV program adopts two key criteria from the national asylum system, which determine eligibility for the pilot: (1) Unsafe country of origin: only individuals from countries officially designated as ‘unsafe’ due to war or persecution; (2) Special reception needs: individuals classified as particularly vulnerable.

Though there have been tensions between local actors and national authorities over what kind of durable solution should be sought by the program, the LVV has de facto restricted undocumented migrants' access to shelters compared with the previous BBB by categorising a specific subset as "deserving", in close alignment with the stringent national asylum system. Individuals perceived as "undeserving" (such as people coming from countries considered “safe”, people with a Dublin claim and other undocumented migrants) find themselves systematically excluded from the program. Moreover, the atmosphere that accompanied the implementation of the new program has also perpetuated an even greater state of uncertainty for most of the undocumented migrant population outside the facilities. Stricter urban policies targeting migrant squatters significantly diminished the legitimacy of migrant squatting movements, for instance, by the We Are Here movement and the possibility of finding autonomous shelter. This is not a new trend. The Dutch state and municipal authorities - not unlike other contexts - have been active for years in dismantling makeshift accommodations while capturing and redirecting migrants “into state-controlled circuits of mobility. However, the first phases of the LVV programme also marked a step up in the fight against migrant squatting, given the logic that people outside the LVV would not be classified as ‘deserving refugees’.

In the current political atmosphere, where fundamental rights of asylum seekers, refugees and migrants in general are threatened severely, our study raises questions about the role of cities in supporting or opposing national government deportation policies. It also questions the underlying logic of assistance at the city level and the importance of maintaining a space for migrants to squat, variably defined as undocumented or unfit for national and local criteria of durable solutions. Their claims reflect a radical critique of intra-European borders and categorisation of safety that should not be silenced in cities that want to play a progressive role in a world increasingly in thrall to restrictive migration policies.