Healthcare

Healthcare

The C-MISE Guidance provides extensive information on practices that municipalities across Europe have adopted to provide access to healthcare to irregular migrants. These practices may offer a blueprint for other local authorities promoting access to healthcare to irregular migrants.

Migrants with irregular status face various obstacles when accessing healthcare services. In many European countries, they may be eligible only to receive emergency care, as various national legislations restrict their entitlements to access treatment. Also in relation to treatments they are legally entitled to receive, they may meet hurdles trying to access healthcare due to practical and administrative obstacles related to their immigration status. For instance, the lack of ‘firewalls’ in national legislation, which exposes migrants attending public facilities to the risk of being reported to the immigration authorities, further deters them from seeking medical care. Moreover, some healthcare systems based on enrolment in a national insurance scheme prevent irregular migrants from obtaining health coverage, ultimately preventing them from obtaining care, including urgent care, due to high costs or obscure administrative procedures. The lack of clarity or awareness regarding the medical treatments available to irregular migrants under national law often deters patients from seeking care. As a result, irregular migrants may not seek medical help until their medical condition deteriorates to the point where emergency treatment is needed, which is riskier and more costly for hospitals than preventative care.

As per international human rights law (Art. 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights), authorities at all levels of governance are required to ensure the fulfilment of everyone’s right to health. This is even more so for the most vulnerable individuals, such as children, pregnant women, the elderly, disabled individuals, those with chronic diseases, including irregular migrants who often experience utter destitution. As made more evident by the COVID-19 pandemic, providing access to healthcare to all segments of society and being able to interact with all potentially ill residents is also a matter of public health, in the interest of the whole community. Providing trusted and safe access to care, may prevent the spread of communicable diseases locally, including for instance COVID-19. In addition, where preventative and non-urgent care is provided, this proves more cost efficient instead of emergency services for public finances and releases pressure from vital services.

Local authorities, where responsible for healthcare, can play a key role in facilitating access to healthcare for irregular migrants. Some have established ‘firewalls’ reassuring migrants seeking healthcare from the risk of being reported to immigration authorities, thus increasing trust and access to local health facilities. In other cases, local authorities have increased the levels of treatments available to irregular migrants by setting up or supporting medical facilities dedicated to offering healthcare to these migrants beyond national entitlements. When high costs of care are the main obstacle to accessing care, municipalities may provide a safety net for migrants who are excluded from health insurance coverage. Municipalities may, for instance, make budget reservations and provide funding to cover the expenses incurred by patients and hospitals for treatments offered to uninsured individuals, irrespective of nationality and immigration status. In addition, if migrants tend to refrain from accessing care because of cumbersome administrative procedures or requirements that are difficult to meet for certain irregular migrants (such as having a fixed address or certain identity documents), municipalities can, in partnership with NGOs, develop simplified procedures refraining from requiring documentation that irregular migrants may not be able to produce.

Latest C-MISE guidance

- Migrants with irregular status face a range of obstacles in accessing medical treatments necessary for their well-being and the public health of the communities they live in. Their entitlement to treatment may be limited by national legislations allowing for only minimal access to public healthcare.

- In several EU countries, irregular migrants may be entitled to emergency care but not to primary or secondary care, nor to the possibility of registering with a general practitioner (GP) and obtaining continuous care.

- People with irregular status may also not be able to access healthcare they are entitled to because of practical and administrative obstacles related to their immigration status. These include the lack of ‘firewalls’ in national legislation, which exposes migrants attending public facilities to the risk of being reported to the immigration authorities and deters them from seeking medical care.

- Moreover, in healthcare systems are based on enrolment in a national insurance scheme, irregular migrants may not be able to obtain insurance because of their immigration status. They may thus be prevented from obtaining care because of inaccessible costs or administrative procedures.

- Uncertainty concerning the medical treatments that irregular migrants can access under national law (or for which they might be eligible to obtain reimbursement) deters patients from seeking care, and medical doctors from providing treatment (due to reluctance to take patients with irregular status or concerns about payment).

- The result is that irregular migrants may not seek medical help until their medical condition deteriorates to the point where they need emergency treatment, which carries risks for their life and health and the health of those around them, as well as higher costs for hospitals, which bear the expense of emergency treatment rather than (less costly) preventative care.

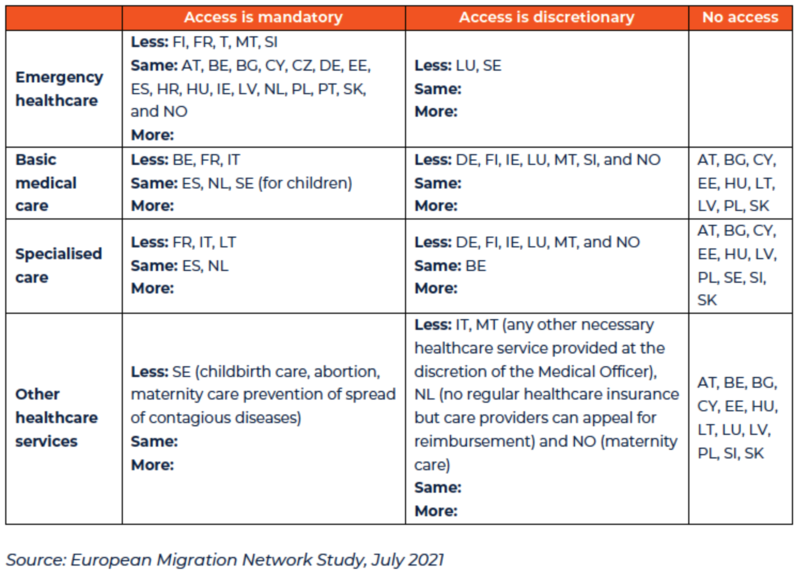

- The results of a 2021 survey of all EU Member States by the European Migration Network indicate that in all but two EU countries, irregular migrants have, on paper, the right of access to emergency and basic healthcare services.

- Only in Bulgaria and Slovakia is irregular migrants’ access to healthcare limited to emergency treatments which is typically defined to include medical attention in childbirth.

- Fewer than half of EU countries permit migrants access to specialised or secondary healthcare services, and where access is granted this is mostly on a discretionary basis and may be subject to wide variation at regional levels or even local practices within countries.

- The results of the EMN survey are displayed below in Table 2 and the nature of irregular migrants’ rights is shown in comparison to the rights of migrants with legal status (permission to reside or work) in the Member State.

- Authorities at all levels of governance are legally required to ensure the fulfilment of anyone’s right to health as recognised by international human rights law.

- Beyond an obligation under human rights law, providing healthcare for irregular migrants is a humanitarian issue, especially in relation to healthcare for children, pregnant women, the elderly, disabled individuals, and those with chronic diseases and in vulnerable situations. The hardships and destitution often experienced by irregular migrants makes them particularly vulnerable to such conditions.

- Ensuring that there are no segments of society excluded from access to healthcare is an issue of public health and is thus in the interests of the whole community. If migrants fear going to a public health facility, they will not seek the necessary medical treatments they are entitled to and their medical condition will remain unknown.

- It has been shown that facilitating regular access to medical treatments for irregular migrants, including preventative care, is cost efficient for public finances. If migrants avoid seeking medical help at an early stage they may later require emergency treatments with higher costs for healthcare providers.

- Where irregular migrants needing healthcare have no alternative but to seek emergency services, public hospitals may experience an excess demand on these facilities, with negative consequences for the services offered to the whole population. Municipalities responsible for the management of local hospitals may thus improve the efficiency of healthcare by enabling irregular migrants to obtain non-emergency treatment (e.g. from GPs or pediatricians).

- The right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health (‘the right to health’) is a well-established human right recognised by a number of international treaties, including in particular Art. 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).

- The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (UNCESCR) has clarified in several instances that States have an obligation to ensure that all persons, including migrants regardless of their migration or residence status and documentation, have equal access to preventive, curative and palliative health services.

- The UN Global Compact for Migration, under the objective to provide access to basic services for migrants (Obj. 15), provides an action point to: ‘incorporate the health needs of migrants in national and local health care policies and plans, such as by strengthening capacities for service provision, facilitating affordable and non-discriminatory access, reducing communication barriers, and training health care providers on culturally-sensitive service delivery, in order to promote physical and mental health of migrants and communities overall, including by taking into consideration relevant recommendations from the WHO Framework of Priorities and Guiding Principles to Promote the Health of Refugees and Migrants’ (para. 31, let. E).

- National legislation in EU countries generally restricts irregular migrants’ access to healthcare to minimal levels. All the 28 Member States of the EU (and Schengen associated countries) recognise in law irregular migrants’ right of access to emergency healthcare. In six EU countries, this is the only level of care that people with irregular status are entitled to.

- Children with irregular status may be entitled to wider access to healthcare than adults. However, in some EU countries children, like adults, only have the right to obtain emergency healthcare.

- The concepts of ‘urgent’ or ‘necessary’ healthcare to which irregular migrants might be entitled are interpreted differently in different countries. The Fundamental Rights Agency has recommended that migrants in an irregular situation should, as a minimum, be entitled to necessary healthcare services, which should include the possibility of seeing a general practitioner and receiving necessary medicines.

- Within the Council of Europe, the ECRI Commission recommended that Member States ‘ensure that health service providers do not require documentation relating to immigration or migratory status for registration which irregularly present migrants cannot procure’.

Establishing ‘firewalls’ that prevent migrants seeking healthcare from being reported to immigration authorities by public employees

In most EU countries, medical doctors (including doctors employed by public institutions) have a legal and professional obligation of medical confidentiality that prevents them from reporting irregular migrants to immigration authorities. However, this obligation does not always apply to other public employees in medical facilities, including those in the administrative departments of a hospital, or those working in the local welfare offices responsible for covering the expenses

of medical treatments provided to uninsured patients. Municipalities can develop initiatives that remove the risk of being reported for irregular migrants seeking healthcare, to allow migrants’ access to care and concomitantly ensure that their health conditions are known by health authorities.

In countries where national legislation establishes a general obligation on all public officials to report the irregular migrants interacting with them, local authorities managing healthcare may seek the mediation of external actors such as NGOs to provide the services that irregular migrants would not request from public officials.

In Germany, for instance, although doctors are exempted from the general obligation imposed on public officials by national law to report irregular migrants, employees of municipal Welfare Departments, who are responsible for reimbursing the costs incurred by doctors caring for uninsured individuals, may still be obliged to pass on the details of irregular patients to police, nullifying the confidentiality ‘firewall’ imposed on medical doctors. Several German municipalities have thus found alternative solutions to establish a firewall:

- The City of Düsseldorf decided to externalise medical services by funding an NGO (STAY!Medinetz)146 to act as a GP for irregular migrants, provide medical consultations, manage referrals to hospitals or specialist doctors (including gynaecologists, dentists, ophthalmologists and urologists), and cover the costs of care. By externalising the service, the local Welfare Department does not interact directly with irregular migrants and does not know their names or details, so the obligation of reporting does not apply. As irregular migrants cannot enroll in medical insurance schemes, the municipality has made a budget reservation that the NGO can use to pay doctors’ fees (at a previously-agreed reduced cost). The budget of the NGO is also used to cover the costs incurred by hospitals for treatments to irregular migrants in an emergency. The organisation provides irregular migrants with a form that they can hand to hospitals explaining that STAY!Medinetz will reimburse such costs. The NGO also informed the local hospitals that they can refer to STAY!Medinetz instead of the Municipal Welfare Department to ask for reimbursement of costs irrespective of whether these were patients initially referred by STAY!Medinetz or not, so that none are exposed to risk of denunciation by municipal authorities.

- The City of Frankfurt, in cooperation with an NGO (Maisha), has set up its own municipal medical consultation centre, known as ‘Humanitarian Consultation Hours’ (Humanitäre Sprechstunde) where the only public employee is a medical doctor of the local Health Department (not bound by the duty to report), while other staff work on behalf of the NGO(also not duty bound). The centre operates as a GP, can provide medicines, and works in partnership with a network of specialist doctors to refer patients with more serious health concerns. The cost of the activities of the Humanitarian Consultation Hours are financed by Frankfurt’s Department of Health and the Department for Women, while the Department of Social Care provides medicines. Healthcare is provided anonymously and is generally free of charge but the centre asks for contributions according to the patient’s means.

Setting up or supporting medical facilities offering healthcare beyond national entitlements

In national contexts where there is only an entitlement to emergency care, irregular migrants are not able to register with a GP, and children likewise may not enrol with a paediatrician, which often forces migrants to seek care only when their condition requires emergency intervention. Local authorities may set up municipal medical clinics that operate as GPs and paediatricians, providing specialist care or other treatment that is not provided for by national law. Authorities may also support external actors managing health centres that offer such services.

- For a period of time, the City of Florence (together with the Tuscan regional government) funded an NGO (Caritas) to manage, in cooperation with municipal officers, a medical facility ensuring continuity of care to irregular migrants following their release from local hospitals. The centre would host patients, post-hospitalisation, and provide them with long and medium-term treatments according to an individually structured care pathway until full rehabilitation. Besides its humanitarian aims, the initiative aimed to avoid the saturation of emergency rooms and long-term hospitalisations in hospitals that previously had been delaying the release of irregular migrants from emergency in order to provide them with post-emergency care.

- The City of Helsinki decided to provide, in its public clinics and hospitals, children and pregnant women with irregular migration status with the same health services as Finnish nationals. In addition to the medical services normally accessible in Finland (urgent care), the municipality further decided to offer all irregular migrants treatments for chronic diseases, medicines, medical follow up, vaccinations and dental care.

- In Norway, irregular migrants are only entitled to access ‘necessary care’ and not to register with a GP (a ‘fastlege’). They are also supposed to bear the costs of medical consultations as they cannot be enrolled in the national health insurance scheme. This means that irregular migrants often refrain from seeking help for non-emergency treatments and may not access specialist care. GPs may refuse to care for patients with irregular status and a follow-up on the medical condition of irregular migrants may not be ensured.

- The City of Trondheim has set-up its own ‘Refugee Health Team’ with municipally-employed medical staff providing medical consultations and treatments to asylum seekers, as well as to irregular migrants ‘with an asylum background’. While refugees may register with a GP following a positive asylum decision, those who lose their right to stay following the final rejection of their asylum case can continue accessing the Refugee Health Team as their GP. Services offered by the team include paediatric treatment, mental health support, assistance with pregnancy, medical checks for infectious diseases (such as tuberculosis), and vaccinations.

- In Cardiff, the National Health Systems (NHS) runs an inclusive local health service, the Cardiff and Vale Health Inclusion Service (CAVHIS), in order to address access barriers within the larger NHS, including those stemming from charging regulations. As an NHS institution, CAVHIS provides health care to migrants with precarious status. This includes free health screenings, primary care consultations and midwifery services, and provision of help in accessing the wider NHS. CAVHIS is generally recognized as being a welcoming institution for migrants who might be fearful or unsure of how to access healthcare and, ultimately, a means of orienting migrants within the larger NHS.

- The City of Oslo contributes financially to the activities of the ‘Health Centre for Undocumented Immigrants’, a non-profit clinic set up and managed by independent organisations. The Centre provides irregular migrants with a range of medical services for free which they may not be able to access in public clinics or hospitals without paying significant sums up front. These include medical consultations offered by a GP. After the consultation, the Centre refers patients for primary or secondary care treatments (including dental care) to doctors who have previously agreed to treat on a volunteer basis individuals referred by the centre.

Providing a safety net for migrants who are excluded from health insurance coverage

In countries where access to healthcare is organised around enrolment in a national health insurance scheme, irregular migrants are often excluded from accessing the mainstream insurance scheme and may not enrol (or be able to afford to enrol) in alternative insurance. This in practice nullifies their right to access care, as they may be expected to pay inaccessible medical fees for treatments they are entitled to, including necessary and emergency care.

Municipalities may make budget reservations and provide funding to cover the expenses incurred by patients and hospitals for treatments offered to uninsured individuals, irrespective of nationality and immigration status, thus forming a safety net for those not covered by national health insurance schemes. This funding can be channelled through the work of public or private organisations managing health services for uninsured people. Such organisations can include within their target groups people with irregular immigration status.

- The City of Düsseldorf - besides providing funding for the management of the health initiative STAY!Medinetz described above – has reserved €100,000 per year to cover the costs of medicines and the fees of doctors and hospitals treating irregular migrants. STAY!Medinetz has agreed with the municipality that they would refer irregular migrants only to doctors who have previously agreed that they would bill individuals referred by STAY!Medinetz at minimal cost.

- The City of Vienna financially supports several NGO-initiatives that aim to form a wide safety net for individuals not covered by mainstream health insurance, including irregular migrants and some EU and Austrian nationals. In particular, Vienna’s ‘Social Fund’ contributes to the funding of AmberMed, an NGO-managed health clinic for uninsured individuals. Their target group includes irregular migrants and unsuccessful asylum seekers with no alternative medical insurance. AmberMed acts as a GP and has developed a network of about 80 specialist doctors (and one hospital) to whom uninsured migrants can be referred, and who have agreed to treat AmberMed’s referrals for free. Some treatments are directly offered at AmberMed’s clinic, including treatment for diabetes. The City of Vienna also funds a health clinic for homeless people who have difficulty accessing mainstream medical services. It is managed by the NGO Neunehaus, which does not differentiate in terms of access to its services by migration status. Neunerhaus and AmberMed work in close contact to avoid double treatments and refer to each other’s medical cases according to the patients’ personal situation and the treatment needed. Finally, the Vienna Social Fund supports an NGO-managed mobile clinic (the ‘Louise Bus’) to reach out to uninsured individuals in night shelters and the city’s most sensitive areas. The Louise Bus offers medical consultations and basic treatments, and provides information on the possibilities of obtaining treatment at AmberMed and Neunerhaus.

- The City of Warsaw offers public grants for providing assistance to its uninsured homeless population. Grants from Warsaw City and Province have been funding 40% of the activities of an NGO (Doctors of Hope) which operates a health clinic with volunteer doctors who in 2015 treated around 8,000 uninsured residents.

- Several municipalities in the Netherlands, including Eindhoven, Amsterdam, Nijmegen and Utrecht, support local NGOs that provide medical assistance to uninsured migrants and cover the cost of health services that are not covered by the ‘National Basic Health Insurance’, such as dental care and physiotherapy and fees for pharmaceuticals. Local NGOs also facilitate access to dental services by connecting patients with dentists willing to treat them for a reduced fee.

Simplifying administrative procedures to access healthcare and refraining from requiring documentation that irregular migrants may not produce

In several EU countries, irregular migrants may need to undergo cumbersome administrative procedures to access the healthcare they are entitled to under national law. These procedures may constitute a significant barrier for migrants who are irregular (especially if they have no fixed address), as they might be required to show documentation that they cannot procure (e.g. related to their residence or a social security number). In addition, irregular migrants may be impeded from accessing medical treatment promptly when urgently needed because of time-consuming administrative processes. Local authorities responsible for the management of healthcare at the local level may develop simplified procedures that take into account the challenges that irregular migrants may face in meeting certain procedural requirements.

In Belgium, for instance, the welfare departments of local authorities verify the requirements to access a dedicated national coverage scheme for patients with irregular status (the AMU/DMH scheme). While some municipalities have developed complex procedures which are difficult for irregular migrants to meet (including house visits by a social assistant to verify local residency which can last up to one month, irrespective of the urgency of care, and may not be possible for irregular migrants who may not have a stable housing situation), other cities have opted for more simplified procedures that take into account the particular conditions of irregular migrants without documentation:

- The City of Ghent, following a recommendation from the Belgian Ministry of Health, has developed a flexible procedure to issue a medical card for irregular migrants and has eased requirements and decided to rely on alternative types of evidence to verify them. This includes testimony by trusted local organisations as to a migrant’s residence in the city and their condition of destitution. Furthermore, to secure swift payments for doctors (and so avoid reluctance to treat patients with irregular status), the city reimburses doctors immediately for treatments provided to patients holding the card and only later requests reimbursement from the federal government under the AMU/DMH scheme. This reduces the waiting time for payments from six months to one week. Doctors thus trust that they will be reimbursed for treatments offered by people holding Ghent’s medical card.

- The municipality of Molenbeek (Brussels) arranges (and bears the costs for) an initial medical consultation as soon as an irregular migrant requests medical assistance, without requiring first that the conditions for AMU/DMH eligibility be met. This considerably reduces administrative barriers and allows for rapid detection of serious illness.

In the Netherlands – where destitute irregular migrants may seek reimbursement for the costs of only some treatments (see above) – it can be difficult for health professionals to determine if someone is eligible for reimbursement. Complex bureaucratic systems for reimbursement can make doctors and hospitals reluctant to treat patients with irregular migration status.

The cities of Eindhoven, Amsterdam, Nijmegen and Utrecht contribute to the funding of local NGOs that, besides supporting the medical costs for irregular migrants, certify migrants’ eligibility for reimbursement and provide them with a note of confirmation to present to hospitals and doctors.

Regional governments in Europe often have the power to adopt regulations and legislation that can effectively expand the entitlements of irregular migrants regionally – an option often not available to municipalities which have only implementational, organisational and administrative prerogatives in the provision of health services.

Several regional governments in Europe have indeed adopted regulations expanding irregular migrants’ entitlements to health care. This is the case for several Spanish ‘Autonomous Communities’ which – in response to a 2012 national reform of the Spanish health system severely restricting access to healthcare for irregular migrants – approved regulations re-expanding migrants’ entitlements at regional level. In some regions, including Andalusia or Catalonia, local regulations re-established equality of access to healthcare with Spanish nationals for all migrants, regardless of migration status. In Catalonia, the Autonomous Community (‘Generalitat’) approved several regulations that attached access to universal health care services to registration with the municipal registrars (‘padrón’) of Catalonian cities, rather than to immigration status.

Similarly, in Italy, several regions, including Puglia, approved regional legislation allowing irregular migrants to enrol with local GPs. Italian regions also reached an agreement with the Italian government to adopt legislation in each region allowing the registration of irregular migrant children with paediatricians.

In Sweden, at least six regions took the opportunity, offered by a national law, to extend access to health services for irregular migrants to the level of Swedish nationals.